Critical Correspondence

- Comments Off on Daria Fain and Robert Kocik in conversation with Thom Donovan and Alejandra Martorell

- Conversations

- 11.8.08

Daria Fain and Robert Kocik in conversation with Thom Donovan and Alejandra Martorell

The Extent to Which and the Prosodic Body

Download this conversation as PDF

Alejandra Martorell: Thom, do you want to introduce yourself very briefly so we know who you are?

Thom Donovan: Let’s see, I’m a teacher and writer. I live in New York City. And I’ve known Daria and Robert for a few years – we collaborate sometimes, and share an economy and an ecology.

Photo: Courtesy of Daria Fain

Prosody

Alejandra: You mentioned some of the questions you were setting out to ask. I wonder if you would start with the general question about the Prosodic Body.

Thom: I thought it would be useful for a readership to hear what the Prosodic Body is in brief. A few years ago (and somewhat still today), something kind of fashionable in the art world and theoretical exchanges was Gilles Deleuze’s idea of the “body without organs”. The body without organs was a political gesture on Deleuze’s part, since it is a body that cannot be hierarchalized, or ordered through traditional categories of thought. I think the Prosodic Body is something different than the body without organs, yet I think there are also radical political and social implications about the Prosodic Body. So, the first thing I’m wondering is what the Prosodic Body is, and how the Prosodic Body may be projecting a political-social body that you both would want to have?

Robert Kocik: Already there’s a lot in there. The body without organs is not something I work with. To my reading, that goes back to Artaud, who was in so much pain, the need to live without organs became crucial. The Prosodic Body would be very contrary to that—to live with our organs and in the fullest sense possible. It tries to recover a sense of organism that we still have never had, certainly not in an American body. And this is very much where Daria’s work and mine coincide.

Alejandra: What is it to live with a body with organs?

Robert: To be as attuned as possible. Let’s just say that everything works by vibration. The amount of the spectrum that we can see is a matter of the organs—of the eye organ. We can see a certain amount of that spectrum, and we hear even a greater amount of that spectrum. But again, that’s another organic system. Everything is conveyed through vibration. The pick up is very limited through the organs—sense, sight, touch, skin. So, the prosodic body is a research and a practice of opening up to the full spectrum. In order to do that, you would be literally where all being is coming about. So being there, where all being is coming about, for me is prosody.

Daria Fain: There’s a fundamental first thing to be said about the organs and the not organs. What you said about Artaud is really important because denying the organs—because of the pain—was a way to redefine what unity of being was. In the same way that you have the humors in the Greek times, the organs are the different spirits inside of the body, the different emotions inside of the body. They are only interesting to consider in how they create an organism and how they function as a whole. By understanding what they are and their functioning as a whole, you can find a unity that is beyond the organism. But if you don’t, scatterness obstructs what is attunement. Artaud wanted to deny the organs because he was looking for this unity. In his reference to Balinese dance or extremely codified theater, he was trying to go beyond the personal to find that unification through language as the major…

Thom: Organ.

Daria: Yes, exactly.

Thom: That leads me to a sub-question, which is something that originally brought us together in conversation—Medieval, Islamic angelology. In such systems of thought there is a lot of discussion of subtle organs, of organs that are not visible and yet intuit a lot and take in a lot of information. How do you see subtle organs as part of the whole of the Prosodic Body, or the whole of what the Prosodic Body is bringing into being by activating?

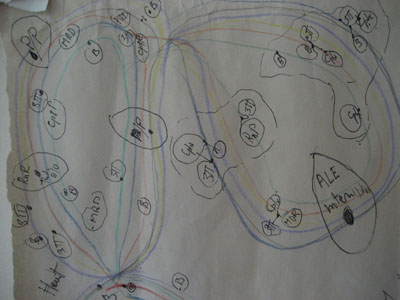

Robert: What is being mediated in angelology is the sensible and the intellectual, and that’s being done with a mediatory organ, which I think is best described in the writings of Henri Corbin, and his use of the term ‘imaginal’—the imaginal world. The prosodic indeed mediates all levels of being: chemical, biochemical, biospherical, celestial, social, archeological, interpersonal… In that the prosodic organ is the very interchanging of all levels, it renders Corbin’s system rather simplistic in relation to what we are moving toward. For me there’s a huge difference (and this is where it’s easy to get stuck in American poetry) between respiration and breathings—the one is physiological and involuntary while the other is energetic. To confuse them is for me disastrous. But to mediate them opens up all kinds of possibilities. It takes an entire body in order to speak. Patterned breathings highly aware of their specific influences throughout the body are energetic. Initially languages were formalized from poetry, which contained, carried or simply ‘was’ such awareness. There are quite a few systems with which you can open up this sense of prosodic body. The nadis, for me, are the most precise, wherein there are 72,000 circuits in the body and one major channel from the perineum to the pineal gland. That channel happens to be the language channel, especially unspoken or unstruck language. Now, if that’s not prosodic, I don’t know what is.

Alejandra: Can you now articulate what prosody is?

Robert: Yes. It’s so obvious and ubiquitous, it is almost impossible to say anything more or anything simpler about it. By now I’ve whittled the word down to ‘vibe’. Prosody is vibe. Something that is good for people to hear is that prosody is typically defined as the elements of composition of poetry—pause, stress, cadence, assonance, gestures, rhythm, the implied, the raising of an eyebrow—everything other than the literal meanings of the words themselves. Now, everything other than meaning with which you communicate is generally considered to be about 80 percent of how we communicate. Meaning, in the prosodic, is a very thin slice of the way in which we come across. So, once you open up the prosodic, you open up a great field of interrelation.

Photo: Courtesy of Daria Fain

Tradition, formation, memory

Daria: In the way we work with Robert, his approach is about how the word manifests as itself, encountering the whole aspect, which is internal and unsaid. But my approach is more directly the seed of how it manifests. For me, the body is like a book—the body is there to manifest. Language—whatever it is, whether it is movement or speech or emotions, anything you externalize—is coming from this book. And that book is a book that is very much made out of layers and layers and layers and layers of memories that are in the cellular, in the genetic. The prosodic body is the understanding of how to manifest that memory in relation to the present or the future.

Thom: Something that always makes me pretty envious and admiring of your projects is how much knowledge and research you both synthesize, and how much you draw into your orbits. Recently you had a residency with the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council in which you built an ancient Greek architectural space called an “abatton”. You also have plans to build another ancient Greek space called “asklepio”. I want to call these appropriations, but I think they’re something different than appropriations. How do you relate these “extra’ or “other” cultural forms or practices? Why are they so important to your own work?

Daria: For me, it’s a very long story. My approach to the body and how I’m trying to penetrate that book of the body has been a matter of learning through disabilities. I started to work with psychotics and with the deaf and blind. The difficulties and impossibilities were actually teaching me. From the disability you find resources that you don’t know. This access to resources you don’t know is very much part of my process of creating a body of language of movement. The piece I made in 2005 (Every Atom of my Body is a Vibroscope) was about how language is formed in the body, and I used Helen Keller as a way to understand how you access meaning. Through that work I really discovered that through the disability, you access the same knowledge that any other being has. So, where does that knowledge come from? For me, that knowledge comes from that book that you can enter into, and that reveals what meaning can be.

I worked with Min Tanaka, an incredible choreographer who worked a lot blindfolded. Then I came upon this residency in Thailand where I was in the dark for a week. Then I was in Greece for two and half months, and Robert came with this hunting he wanted to do about “asklepions”. We found that there were these healing practices in darkness related to dreaming. I think it was a key moment for the Prosodic Body because we came up with an architectural archetype of the vision of what the Prosodic Body could mean in terms of a place. This is how the LMCC project came about. It started a long time ago, in 2005, when Robert came up with the subtle bodies. But the trip in Greece was an architectural revelation of how to manifest architecturally those concepts of space. One connecting with the unconscious and memory, and the other space, found at the asklepion sites—a projecting space, the amphitheater. After we went to Greece, the paradox between the two was very clear.

Robert: How and why we turn to history and tradition…that’s a vast subject. Even what we do in New York City, the extreme degree to which we are just winging it and working from scratch, is barely influenced by our heavy reliance upon the past. We constantly look for things that confirm or fulfill what we need to do. So there’s always an interesting balance going on there. To zero in on the “asklepion”: we were in the Aegean and in Peleponesia on our pilgrimages, clearing these sites out of the brush, hopping over fences to places that weren’t accessible to the public (or apparently anybody at all) for a long, long time. Though they are indeed architectural sites, they were always founded on a particular ground for a profound reason. The architecture arose from some property or presence at the site, which when I was there, that was what I was there for. The architecture is in ruins or almost completely gone, but that site is still there. So there we were at these sites, and what happened to us was very remarkable, in every instance. We would crash a gate and spend long periods of time sleeping, meditating, being still, going through all sorts of changes, rematerializing and repatterning in absolutely unpredictable ways. I would be driving Daria crazy. We would be staying in motels in between transmutations and I would be keeping the asklepian rituals, wrapping myself in motel carpets on a terrace all night, not speaking, not eating. We were both like displaced people, and our biochemistries were altered utterly.

What I was struck by is that the sites are entirely active if you’re tuned to them, if you keep the interaction, stay with the intimation. And beyond that, what I found was that the experience was invariably nothing like what I was prepared for or expected. I would have thought that it would have had something to do with imagery or memory because the epiphanic world or dream is the basis or core of “asklepian” healing. And what happened in fact, at least in my case, was entire biochemical rearrangement, reanimation, or, perhaps deanimation—a change of state. The name or narrative that might account for the experience was incidental to the actual change of state.

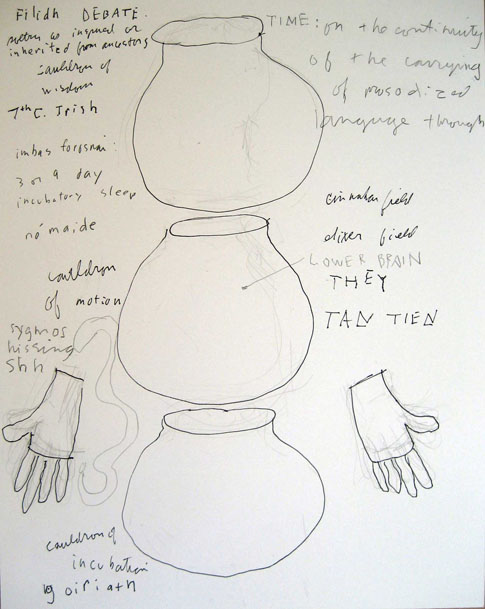

Finally, it’s very linked to Artaud. With that degree of embodiment, one thing that opens is the ability to be outside of your body—a body bypass. As with shamanistic traditions, for example, leaving the body is a great vantage point for seeing and healing. It’s the best thing in the world for you if you’re sick: to get out of your body in order to remove any interference and let the body take care of itself and do what it does best. Artaud, Asklepios, are keepers of the prosody. Prosody is a stream that runs back to Taoist internal alchemists and forward through Parmenides, Abhinavagupta, Parcelsus, Medieval Irish fili, Emily Dickenson, right up to Pauline Oliveros. For example, in the East there are the 3 tan tien or furnaces, while in the West we find the three cauldrons of the Irish poets—one in the groin, one in the heart, one in the head—for pouring energy or medicines or elixirs from one part of the body into another as a form of instruction. Prosody is the stream of correspondences the prosodic body draws from.

Thom: Another thing that Robert brings to your collaborations is a practice as a builder, a designer of spaces and furniture, and an architect. How do building physical spaces enact prosody as a healing practice? Then again, I think there’s something more than just healing at stake, which goes back to the philosophical and spiritual traditions that you’re talking about—a potentialization of space, of the body, of worlds. This goes back to all that Medieval stuff—Zooastrian degrees, Spinozan modes and attributes, potentia versus actuation. Could you talk briefly about the Prosodic Body in terms of potentialization?

Daria: The first enactment of the body, the person, is to relate. The moment that you do something, like putting an object somewhere or relating to your environment to protect yourself—this first need to differentiate the inside from the outside or to create a configuration in space—is an architectural gesture. But how are you going to do that is the question. How are you going to determine that something protects you or is against you is how you feel internally. This notion of creating the permeability between the material space and the body and how we feel is something primordial to us in terms of understanding how we are reading ourselves in physical space.

My first impulse when I studied Indian dance was to go to India to understand the correspondence between the classical Indian dance of Barata and South Indian temples because the treatises on creating dance and architecture are completely related. (The principle book is the Natya Sastra.) I got really fascinated with the history of the architecture of theater as a manifestation of how people were seeing the body. People throughout the centuries were framing the body differently in the architecture of theater. I went then way back inside the Chinese energetics to understand the internal aspect of that—how the internal aspect of your organism is defining how you are going to feel in relation to architectural space, and how you’re going to connect or disconnect, react, inhabit. It’s very simple: if you’re angry, you’re going to have a very different approach to the space that surrounds you—you’re going to reject it, you’re going to go to a corner, you’re going to pull into the space. If you’re feeling sad, you’re going to have a very different relationship to the floor. All those emotions are defining a relationship to the physical space. This is a very obvious connection for me.

Robert: There’s a lot of overlap there [between us]. In terms of building, being very committed to material, I was already a completely enlightened esoteric being as a teenager. I say this in all modesty because I think everybody was/is. And then you have the opportunity to lose that, to keep that, to mess it up, to scuff it up. Looking at being-already-complete, it becomes a kind of dead end too—what are you going to do? You look at your watch and say ‘I have perhaps another 70 odd more years here, I might as well get my hands dirty, right?’

The clear path for me was to go against my aptitudes. A little engineering, picking up the practical trades… the commitment is to stay behind, in material, in building the world, which is where all the suffering is. To be charitable it’s essential to become as resourceful as possible, as skilled as possible, so you have more to transform with entering into situations. The problem in America is that you’re given the opportunity not to stay behind, you go ahead because the American spirit is promoted as goodgreed, individualist buccaneerism. Getting ahead here means being well to do. Conversely, there is transcendence and the ascetic—no need to get involved because you’re above it all. The other way is to stay behind. Even soldiers know this—the creed of the soldier to never leave anyone behind… not even a corpse. This is understood because the situation is a matter of life and death, so the soldier is vowed to go back and get anyone left behind. This is what American can’t do. You get ahead and you stay ahead and you get further ahead, and you think your success will raise everybody else but it never works and it will never work. It’s the failure of America. Nobody stays behind until all advance together—that’s taken as leveling socialism or, even worse, totalitarian erasure of individual. It’s heretical to stay behind. But my life with materials is only that—you stay behind, you get soiled, and you build stuff, if you can, and try to make the world a world we’d rather live in. This is my relationship to material as a medium. If I try to bypass that, I bypass my body and I loose my medium as an artist. So, my first business, which is still my business, is called the Bureau of Material Behaviors—which correlates micro-structure or materials, material behavior and our behavior. What we do with material is a portrait of ourselves as a people.

Photo: Courtesy of Daria Fain

Liberatory language

Thom: An outshoot of the Prosodic Body is the Phoneme Choir, which is a choir of 40 people who each are responsible for one individual phoneme that according to Rudolph Steinberg makes up language as a whole. Something that interests me is to place the phoneme choir in the tradition of performance and composition, particularly music composition. I think this genealogy goes back most specifically to folks like Jackson Mac Low and John Cage. One can also relate it to the practices of poets like Robert Duncan—whom Robert studied with in the Poetics Program at San Franciso State in the early 80s—and Susan Howe, who like Robert has much to say about the violent histories of the English language. In fact, I think one of Robert’s most original and profound propositions regarding the Phoneme Choir is when he says “the English language has never been free”. How is the Prosodic Body investing language with liberatory, if not anarchic, values?

Robert: In response I’d ask ‘what was the occasion, the opportunity or the mandate for English historically as it founded its vast empire?’ For me English was to finally be the language that speaks truth to plutocracy, that uncorrupts money and that makes material existence a non-hindrance for all forms of development. Its ‘moment’ was to accomplish all these things. And it’s failed on every account—to be the famous democratic tongue. English as a non-liberated phenomenon, is first of all, a stress-based as opposed to tonal language. It’s assertive, it’s insertive, incendiary and insistent. It’s imperious, persuasive preemptory and predominantly predominant. It’s a brash, blow by blow, face value only language. It’s an upstart, over-oiled, poparted, haughty, hoity-toity, crotchety, curnudgeoned and slummed tongue. It is above all and has never been other than mercenary and commercial. It’s a kind of forked plain talk wherein you put your own self-interest first while giving the impression of fairness. It’s how America shows up at your shore. It’s a perfectly dichotomous list of possible side effects. It’s the duplicitous terms of credit agreement. It’s the language of bail out that never meant to free up money for lending to everyone but was from the start intended as a safety net for the few who caused the fall. Whitman was fond of saying that English had ‘pluck’. I take this pluck as a given that can no longer be granted its privileges. If for example, the current economic and climate crises are inevitable outcomes of the intrinsic qualities of English, how can American poets now operate on their native tongue? This is the global language and we are its epicenter. English is the centerpiece of globalization. My work with the Prosodic Body and the phoneme choir is to make emanate from English qualities and outcomes that have not yet been intrinsic to it.

Traditional languages…that are subtle, that are initial—their origins are lost in prehistory, but the kernel of English is right before our eyes. The three long boats came over from the continent, from the Western Germanic peoples in 449AD, and by the end of the 7th century you have the first English poetry, and the first written instance of English speech, in the same person, right, in a poet, Caedman. Caedmon has a dream. He’s illiterate and he’s very ashamed of his illiteracy. He is a stable-keeper. He runs away from the party because he can’t sing rounds. He falls asleep in the hay and is told, in a dream, to sing. He sings a nine-line creation hymn. Our poor little English theogony. True to prosody, English poetry was born in dream to the humblest of men. And what we’ve made of it to date is this rapacious, global, growth. So, a lot of work to do as poets, and the phoneme choir is an attempt to break the language into bits and infuse it with properties it has heretofore never had. I call it re-English and the phoneme choir is a key piece of that.

Daria: Because I’m not a native English speaker, this is a very interesting thing for me. When Robert came with the idea of the ‘commons’, this is where it really hit me—that language can be a base of reflection into what we have in common. What is the commons now? We don’t have a land in common. We have the accessibility to language and maybe that language can help us access what we have in common in terms of our internal being—our genes. If we can use the phoneme choir not only as a performative embodiment of that which we have in common, then that would be really amazing. It goes back for me very much into the tradition of Greek tragedy with the chorus, and the relationship of the chorus in Greek tragedy as the intermediary between the hero and the people. That’s what I seek as performative form—to connect to. What would be the form of a chorus now? What would a chorus say about our time, in terms of where we are at, what we need to transform as social beings? It’s not an easy answer in terms of how we go about it, but I want to use the idea of the phoneme choir also as a forum of working with those issues.

Robert: It’s not unlike a physics experiment. You break something down into its basic elements so that other influences can waft in. In that the phonemes are awarenesses, they are energies, they are constituents of the physical universe. If you open them up in English, you give English speakers tones they’ve never known, by becoming aware of the forces of the sonic aspects of the language as a full approach to life. We didn’t have century after century of mantra and scripture, and focus just on the vibratory qualities of language and what they do to the body. English hasn’t practice the 82 points on the roof of the mouth that can be tapped open by particular sequences of syllables in order to set off particular physiological effects. If you break the language back down to its basic elements, maybe there’s a chance that moving forward can be starting over.

Photo: Courtesy of Daria Fain

The Extent to Which, presence and choreographic enclosure

Daria: Also, this idea of simplification of the language, like for instance American. It is actually a really complex process being driven to reduce it to action: go, come, this… We do not look at the complexity of the simplification process. Therefore we loose the memory. This is for me very much connected to how we see the body as well. The simplification of the language is because there’s also a simplification and numbness about the body itself. The access of the complexity, the multiplicity of what words are, resonates into the body as a rich organism that can be the most simple, still and empty to the fullest. And that range from fullness to emptiness is really complex. This is where performance comes in for me. How do we express that range? And that’s what I’m trying to do with The Extent To Which.

Alejandra: I’ve heard you say, ‘it’s not what we as performers experience; it is what we decide we want the audience to see or experience’. I’m not saying it like you say it. I’m interested in what that means. How you arrived at that framework?

Daria: I’m going to make an analogy, it’s like when you have an idea. Before you are able to articulate it, to communicate it, you go through a process of thinking, and that process of thinking is very interesting, but it’s not interesting to communicate it to an audience, unless you’re in a situation of one-to-one. That’s what we do in rehearsal—I give you a concept, you tell me what you think. But ultimately it is for you to be on stage and to translate this idea to the audience, and if you are able to articulate it, you are able to articulate at the same time your process of thinking and how you’re saying it. That’s what I want. But I don’t want the performer to be searching in himself what it is. I want the performer to know what it is, and to work toward how to communicate it.

Alejandra: Does that have to do Robert with something that I picked up from this paper that you forwarded, when you talk about inner and innards? [“A Way in Which Space Works,” a talk presented at Judson Church in the context of the Movement Research Festival 2004.] Does the performer looking for things versus the performer knowing and articulating, reflect in any way what you were talking about there? You were also talking about presence and doing a diatribe on presence.

Robert: It’s not that I think presence is overrated, but I can think that performance relies on it too much. If you have any kind of reduced presence—selfish or egoist or technically poor in that it’s just bodies on stage in front of an audience—just as stars, when they don’t have adequate fuel, they collapse into themselves. And what they do when they collapse into themselves is draw everything in from around them. So, in this analogy, the audience is an in-falling object into a presence that doesn’t have enough energy to keep its form, so it collapses, and when it draws the audience in, they’re deformed, and the effect is called ‘spaghettification’.

Alejandra: Is it about energy, enough energy, or is it about what the performer is doing—whether the performer is searching or the performer is knowing, doing and articulating? Another way you’ve put is would be that the performer is in the process of being in relation to the environment, as opposed to being fueling this thing that we call presence.

Robert: Yes, I think that’s a better ecology; I think that’s more what Daria does. It’s the integrity of the relationships you are in at that moment, not just with regard to yourself—to your innard or your inner—but to the outward. If the performers are using material—the integrity of their relationship to the design of the costume or the surroundings. The entire surround becomes part of an expanded sense of presence to get away from the collapse and reduction of presence. There’s a sense of purpose in their movement given by the choreographer but also picked up and brought to life by the performers. Then there is an entire environment of awareness moving on the cues that are there, created in the interaction with the performers. Then you get something that doesn’t collapse.

What would be the contrary to spaghettification? Fully non-deformed form? Spaghettification is the contrary term because when you get drawn into the collapsing energy, you’re elongated, and instead of human beings every body looks like a Bacon painting. Everything disappears in a collapsing energy. What I go on to say in the article you’re referring to, after I make the point about spaghettified presence, is the fullness of space. I’m specifically referring to Daria’s work as a choreographer as she works with you and the other dancers.

Alejandra: “Cognition of the non-habitual and non-recurrent defines performance”. That to me spells out what I feel when I see really engaging work because it’s building something that has never been built before, and will never be built again. It’s meaning but it’s pre…

Robert: What I’m trying to define there is a form that keeps fueling itself, that keeps giving energy, that the more it realizes itself, the more potential it generates, which is contrary to biological form.

Daria: But the question becomes what does realization mean? I find that it’s always a challenge. How do you embody a form?

Photo: Courtesy of Daria Fain

Irrecoverable data

Robert: Recognition of the non-habitual—where I’m trying to get to is this moment that is most alive. I’m trying to locate what is most alive about performance. What can possibly be most alive? When something is coming about, you can’t fool an audience. Another analogy I use is the stem cell. When you’re giving people potential instead of using up potential, as great art does, it’s like bringing everybody back to the totipotent stem cell situation where you can still turn into anything you want. If you were to interview people at that moment (during a totipotent choreographic work), they would say things like ‘I thought of so many things I could do in my own work’ or ‘it made me want to do this’ or ‘it turned my life around’. I’m calling that moment, furthermore, a moment of inception—what was the first verbal act? What was the first motion?

We don’t know, [but] we were not motioned creatures once upon a time, and we most certainly didn’t always have language. What was the initial impulse? This is what choreography can show us. What can be discovered by performers on stage is potentially the most concentrated, necessary science that we have. The knowledge sciences are all going over to the subjective and experiential. Tragically, performers are completely left out of the picture. Why dance is not data for scientists? I’m saying that it is. In a choreographic enclosure you become the irrecoverable data. Scientists, phenomenologists, cognitivists, should be able to go in there and when you, as a dancer, are in your realization of the non-reiterative or the non-habitual, they might suddenly see the original overlapping of the motor and verbal maps being sorted out! The irrecoverable data.

Daria: One of the main things that I always come back to is why the science of dance… centuries of history like Indian dance, are able to do this, while for us it is so difficult. The reason why they can do it is because they really have a language, a language that is extremely codified. The problem with my work I feel is that I want both things. I want to codify everything and to give freedom at the same time. I want the experience of the potential as a science and to also bring in a language that can then be used really by the performers. But this is like an empirical task. I will never be satisfied with it. I don’t think there is a point of satisfaction. There is an exhilarity or exhilaration of the process of discovering what that can be, but the contemporary situation of negating everything that has existed to innovate is a big problem. I feel like I don’t try to be innovative at all. I draw on very traditional forms. But this is conflictual because I draw on these very traditional forms with people who haven’t done these forms. I transmit conceptually what those forms are and try to do a thousand things at the same time, hoping and working toward the possibility that that will create, without knowing what it will create. And that is the big madness about that work.

Alejandra: And you’re clear that there is a reason why you don’t work with already codified languages?

Daria: I actually work more and more towards that. I find that the form of bagua that I found is going to become very predominant for the next few years, and that my next piece might be entirely codified. But even if it’s entirely codified, that codification will always be towards a means of communication among the performers. The experience I just had by transmitting the work to a new dancer was very amazing because when I found myself the first time alone with Benjamin [Asriel], I gave him all the directions that I gave you, but very simplified and he started to do the same movement as Jonathan [Bastiani] (who had done the work for over a year), and I was like, ‘oh my God, that is too much! I know that that can happen since I worked with Amy Cox. Amy showed me that my thinking brings out a very specific language in the body. I do that in myself as a performer. I find that I’m getting closer to a codification that is clearer, but it remains and will remain a question for me. I don’t think this is something I can solve once and for all. It’s my question. What is codification?

Robert: The way I come to this in my relationship to the work the two of you do together: I’m the scribe of the process. It’s amazing language. For me it’s a privilege—I’m privy to that interchange, that live dialogue between dancers and choreographer about form and formation and freedom from form. The sharpest moment of all came the other week when Daria brought out her latest batch of scores . To watch those scores hit the performers was a highlight—the performers (mimicking ‘performer’ looking at score on piece of paper) “which way?” Watching the score come in, and seeing the performers’ reactions to the score on a piece of paper in relation to what they had been doing up to that point day after day, thoroughly disoriented everyone—like being thrown off the path you thought you were on. I especially remember your comments—you’re pointing at the score, and saying: ‘but THIS, this is YOUR choreography, this isn’t OUR dance!’ So, the dancers, in their kind way, making sure they would continue to be creators of the work in a non-hierarchy, just dismantled the score piece by piece until it wasn’t there anymore, and they could then simply get back to their work.

Alejandra: To our presences…